1. Russell Square Underground Station (Piccadilly Line)

The Bloomsbury – Holborn walk begins and ends at the Russell Square Underground station. All venues on this walk are within a 10–15 minute easy walk of each other.

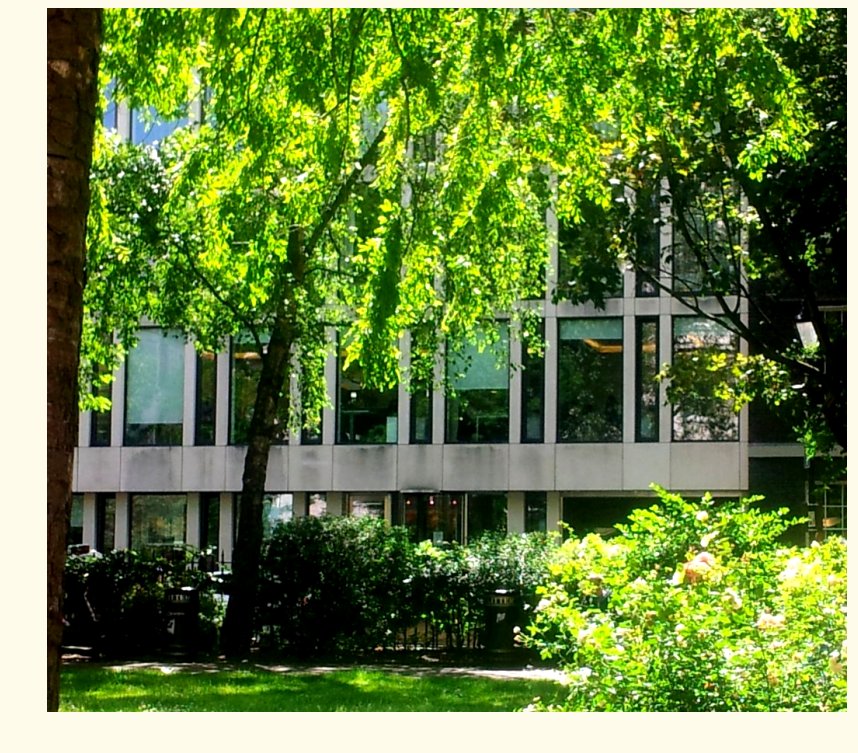

2. Faber & Faber (1929–1971), 24 Russell Square.

From 1929 to 1971, Faber & Faber premises were at 24 Russell Square. The main entrance was round the corner from the Square itself, in Thornhaugh Sreet. Originally the premises were chosen by Geoffrey Faber for the expansion of the Scientific Press. In September 1925, the press then became Faber & Gwyer Ltd. When Geoffrey Faber chose this house in Bloomsbury (partly for its literary connections) he described it as ”rather a fine house; we have got to build up as fine a publishing house as we can to inhabit it”1. Tom Eliot (T.S.Eliot), who was then Editor of the Criterion and had already published most of his best–known poetry, was appointed to the Board of the publishing firm at that time.

In 1957, Ted Hughes wrote to Faber & Faber asking if they might be willing to publish Hawk In the Rain, which had just won the First Publication Award in a contest sponsored by the New York City Poetry Center. Having read the book, Eliot scribbled a note to Fabers’ poetry editor saying that he was “inclined to think we ought to take this man now”2.

So, from 1957 until his death in 1998, Hughes was a ‘Faber poet’. The famous photograph of Hughes, glass in hand among the greats – MacNeice, Eliot, Auden and Spencer – was taken in the Russell Square house.

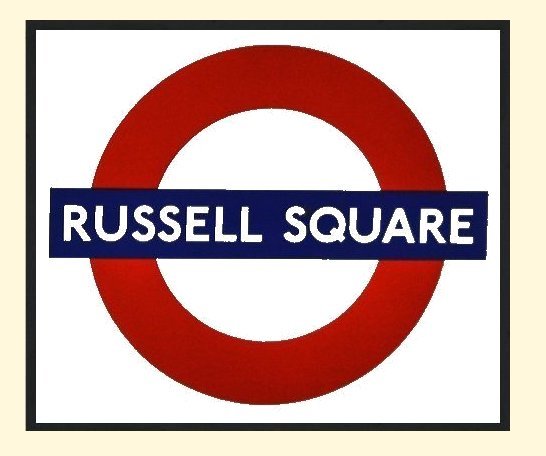

3. The Church of St. George the Martyr, 44 Queen’s Square.

Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath were married in this church on June 16, 1956 – “Bloomsday”: ‘A Pink Wool Knitted Dress’ (THCP 1064)

Both Ted and Sylvia referred to the church of St. George the Martyr as the Church of the Chimney Sweeps. For Sylvia, this seemed a romantic designation. In England a chimney sweep at a wedding was always considered to be a lucky omen.

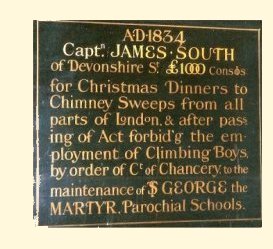

Inside the church, this nineteenth century plaque records the donation of £1,000 by a parishioner for the provision of Christmas Dinner for London chimney sweeps. Generous as this seems, it exemplifies the sort of piety of which William Blake wrote so angrily in his poem, ‘The Chimney Sweeper’ (Songs of Experience). In the 1800s, chimney sweeps were children, apprenticed at the age of seven or eight, to climb through the narrow, tortuous, maze–like chimney flues of London houses. Many died of suffocation. By the age of twelve, most had grown too big for this work and they were crippled, stunted and ill, often with cancer of the scrotum.

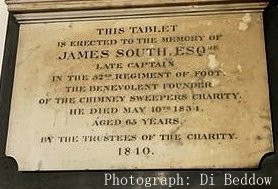

A second paque, erected in 1810 and dedicated to James South Esq., records his founding of the Chimney Sweep Charity.

Many of these children were treated at the nearby Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children. In 1929, James Barrie, creator of Peter Pan, gifted his copyright of Peter Pan (books, plays, and films) to the hospital, and the hospital legally holds the right to any royalty from Peter Pan in perpetuity.

Part of the church has now been partitioned off to make a small cafe and you can see inside through its large glass windows. The cafe is currently closed due to restoration work but the church is open Tuesdays to Thursdays 10.00 - 12.00 unless booked for an event (Sept. 2023).

4. Faber & Faber (1971-2008), 3 Queen’s Square.

Ted Hughes: Selected Poems 1957-1967 was the first of Ted Hughes’s books to be published after Faber moved to these premises. Every book after that (apart from limited editions), including plays, books for children and, of course, Birthday Letters, was published from here. Hughes would have known this building well.

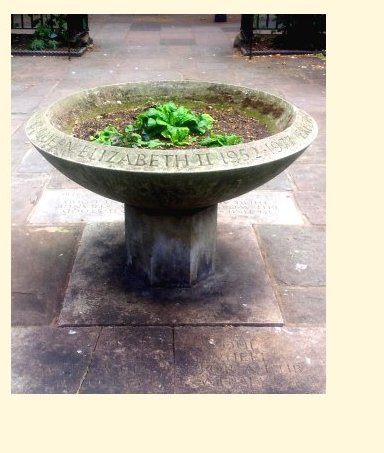

5. Queen’s Silver Jubilee 1977, flower urn.

In 1978 Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin were commissioned to write short poems celebrating the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. These were inscribed on paving stones which are set at the foot of this urn. Ted Hughes’s poem was later published as ‘Solomon’s Dream’ in the preface to Rain Charm for a Duchy (Faber, 1992)(THCP 802). The stone on which it is inscribed is damaged and moss–covered.

6. 18 Rugby Street.

This flat was rented by Daniel Huws’ father who passed it on to his son, Daniel, who used it regularly as a pied–a–terre during college recesses, then later as his home after he was married. Daniel Huws and Ted Hughes became friends whilst studying at Cambridge University and Ted, who completed his degree before Daniel, moved to London and lived in the Huws’s flat. For a time, Hughes worked as a reader for the film magnate, J. Arthur Rank, probably at Rank’s nearby Mayfair premises.

Lucas Myers, in an unpublished manuscript now held in the Pembroke College Ted Hughes archive, remembers that the house was damaged during the 2nd World War air–raids and was condemned, but that each of the four flats was occupied. He also notes that Dan Huws remembers Hughes rejoicing in the fact that Dylan Thomas had once visited the house.

Hughes’s first night with Sylvia Plath was spent at 18 Rugby Street, and he memorialised it in his Birthday Letters poem, ‘18 Rugby Street’ (THCP 1055-8). He continued to live there, making frequent trips to Cambridge, until Plath broke the news of their marriage to her college. In December 1959, after their return from America, Hughes and Plath lived at 18 Rugby Street until they found a flat of their own close to Primrose Hill.

Susan Alliston, who was a secretary, then a reader, at Faber & Faber, is also mentioned in the poem ‘18 Rugby Street’: (“Ten years had to darken….before Susan / Could pace the floor above night after night”). She died of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1969 and after her death Daniel Huws and Ted Hughes found her poetry manuscripts in her flat. Hughes’ ‘Introduction’ (written in 1980) and some of her poems were published in the Saint Botolph’s Review No,23. In his ‘Introduction’, Hughes described how he first met Susan in a lift at Faber & Faber, and how he had got to know her after meeting her again, with friends, in The Lamb. After this she became his close friend for six years4. Susan is the subject of the Gaudete Epilogue poems which begin “I know well / You are not infallible//… ” and “waving goodbye from your banked hospital bed,… ”(THCP 368, 364).

Jim Downer, a commercial artist, was living in one of the flats at 18 Rugby Street when Hughes first lived there. He had written and illustrated a story called ‘Timmy the Tug’, which he showed to Hughes. Hughes offered to write his own verse version of the story but the draft of the book got mislaid until Carol Hughes re–discovered it at Court Green. Timmy the Tug, written by Hughes and illustrated by Downer, was published by Thames & Hudson in 2009 .

Richard Hollis, the graphic designer who collaborated with Hughes and Daniel Weissbort to design and produce the magazine Modern Poetry in Translation, also lived at 18 Rugby Street. He remembers Hughes and Plath but never knew that Sylvia, too, was a poet. He saw her only as “a sort of homebody… who used to just sit doing domestic things, sewing and so on”.

The above quotation comes from an interview with Richard Hollis which is held in Soundcloud. A link to this interview can be found, along with more interviews, photographs, and information about the house and its occupants, on Bobby Williams’ web pages at https://18rugbystreet.co.uk/.

7. The Lamb, 94 Lamb’s Conduit Street.

The Lamb has long been the haunt of poets and writers and it was the much–frequented ‘local’ pub for those who lived at (or visited) 18 Rugby Street. Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath often met their friends there, and Dylan Thomas, Thom Gunn, Jaques Tati, and Peter O’Toole were among the Rugby Street visitors who probably drank there. In earlier years, the Bloomsbury Set knew it well and Charles Dickens, who lived nearby in Doughty Street from 1837–1841, is said to have frequented it. It still has a Victorian interior with etched glass ‘snob screens’ which can be opened and closed to ensure privacy by separating well–to–do customers from the bar staff.

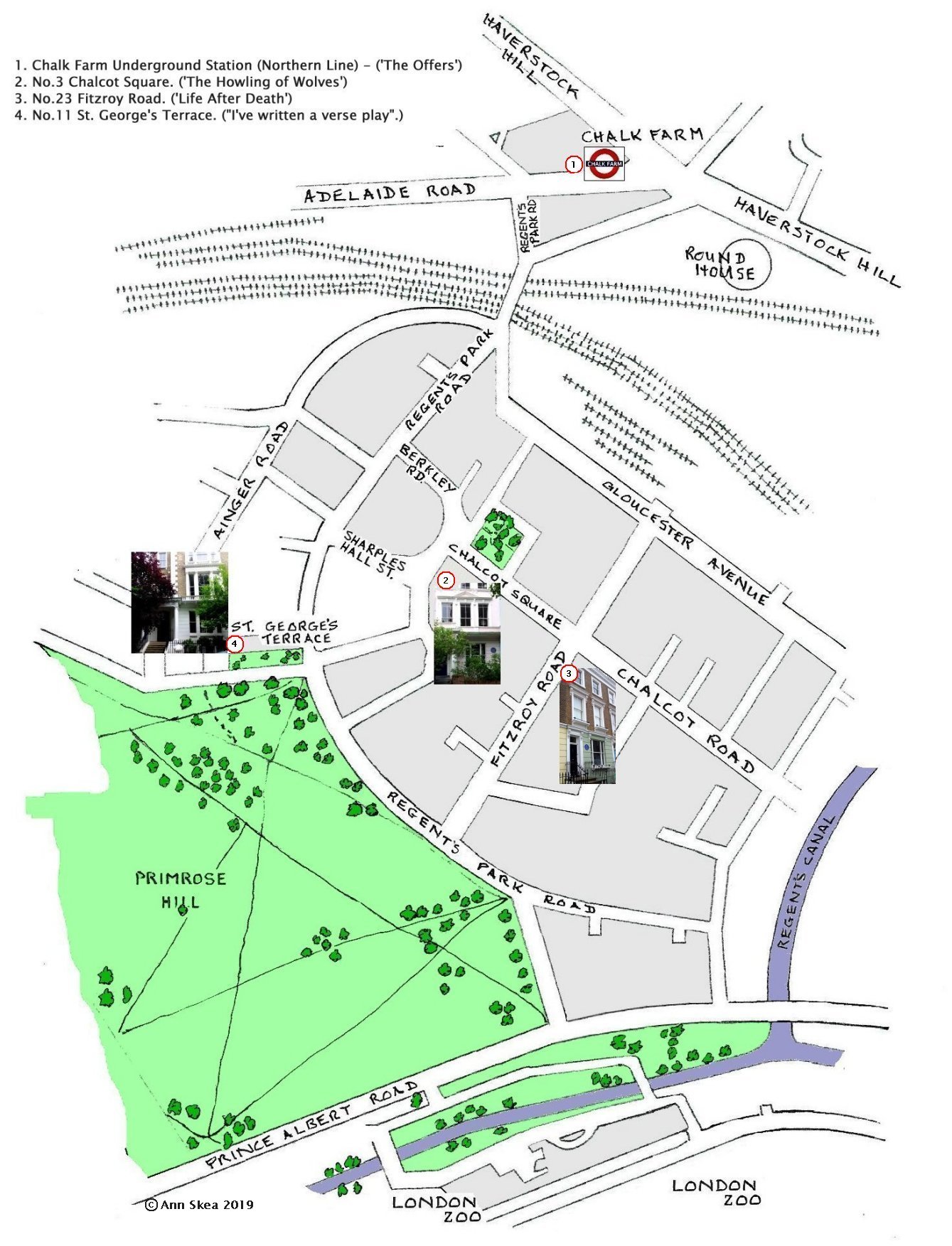

1. Chalk Farm Underground Station (Northern Line)

This walk begins and ends at the Chalk Farm Underground station. If you are coming from Russell Square Underground Station you will need to change to the Northern Line at Kings Cross St Pancras. The journey takes about 15 minutes. All venues on this walk are within a 10-15 minute easy walk of each other.

The exit from Chalk Farm Underground Station is in Adelaide Road. Turn right, cross the road, and take the first turning on the left into Regent’s Park Road (also called ‘Bridge Approach’ on some maps).

‘The Offers’ (THCP 1180–3)

“I got on the Northern Line at Leicester Square

And sat down and there you were… .”

“If you got out at Chalk Farm, I told myself,

I would follow you home…”

“Chalk Farm came. I got up. You stayed”.

2. No.3 Chalcot Square.

In January 1960, Hughes signed a lease for the third–floor flat at 3 Chalcot Square. He told Aurelia and Warren Plath that it was “a pleasant very light flat with one bedroom, one living room, one kitchen, and a bathroom”. (THL 156). Hughes’s writing space was a small alcove in the entrance hall, where he wrote on a collapsible card–table. He told Lucas Myers that it was the best workspace ever, but Bill Merwin described it as a ‘black hole’.

In a letter to Esther and Leonard Baskin, Hughes described the flat as having “an excellent zoo, starting within 100 yards. We hear the seals regularly & occasionally the lions and wolves.” (THL 160). A few years later, Hughes told George Macbeth: “wolves howl in concert, in harmony, and for pleasure” (THL 244).

‘The Howling of Wolves’ (THCP 180)

Is without world.

What are they dragging up and out on their long leashes of sound

That dissolve in the mid-air silence?…

Frieda Hughes was born here on April 1st 1960. Hughes wrote ‘Lines To A Newborn Baby’ (THCP 96).

Lupercal was published in March 1960.

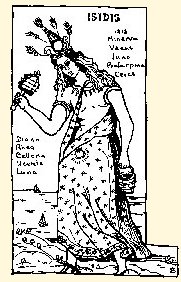

One of the pictures Hughes hung in the flat for inspiration was an unframed alchemical image of Black Isis.

3. No.23 Fitzroy Road.

In December 1962, after Hughes and Plath had separated, Plath moved in to this house in which W.B.Yeats had once lived: “Well here I am! Safely in Yeats’s house!” (LSP 927). Plath rented the top two floors of the house (a mansard roof with extra rooms has since been added).

On February 11th 1963, Sylvia Plath committed suicide.

Hughes immediately moved into the house to look after Frieda and Nicholas. For a short time, his aunt Hilda also helped. Then he employed a nanny. Warren Plath and his wife stayed in the flat shortly after Sylvia’s death, Aurelia Plath visited in June, and Frieda went to pre–school from there. Assia Wevill lived there with Hughes and the children between May and September 1963, when Hughes and the children moved back to Court Green. Assia then lived there with David Wevill until April 1964.

In the pain–filled Birthday Letters poem, ‘Life after Death’ (THCP 1160), Hughes wrote of the effects of Sylvia’s death on the children and himself. Again the wolves at the zoo can be heard:

“We were comforted by wolves.

Under that February moon and the moon of March

The Zoo had come close.”

“Wolves consoled us. Two or three times each night

For minutes on end

They sang.”

“The wolves lifted us in their long voices.

They wound us and enmeshed us

In their wailing for you, their mourning for us,

They wove us into their voices”.

4. No.11 St.George’s Terrace

The American poet, Bill Merwin, who was living in London with his wife, Dido, had become friendly with Ted Hughes. Dido had helped the Hughes’s find and furnish the flat in Chalcot Square, and had introduced Sylvia (who was heavily pregnant) to her doctor. Bill, aware of the cramped and difficult condition in which Ted worked, offered Ted the use of his study whilst he and Dido were away at their farm in France. Between July and September 1960, Ted used this study to write his “tragifarcical melodrama in very rough verse” (LTH 163). This is probably the unpublished play, ‘The House of Aries’. Sylvia (unknown to Bill) also used Bill’s study and wrote The Bell Jar.

REFERENCES

1 Toby Faber, Faber & Faber: The Untold Story, Faber, 2019. p.11.

2. Toby Faber, op. cit. p. 247.

3. David Andrews Ross and Daniel Weissbort (eds,), Saint Botolph’s Review, No.2, Viper Press, 2006.

4 Richard Hollis (ed.), Susan Alliston: Poems and Journals 1960-1969, Five Leaves Publications, Nottingham, 2010. This contains an ‘Introduction’ by Ted Hughes. It also contains diary entries of Alliston’s early impression of Hughes when she met him with friends at The Lamb.